So, the Commonwealth Budget was in surplus in 2022-23, by a much larger quantum than was expected just a few months ago —0.9 percent of GDP compared with 0.2 percent as estimated in May Budget. This makes Jim Chalmers the first ALP Treasurer to deliver a surplus since Paul Keating, but the red is expected to return from 2023-24. Does this mean we have a long-term fiscal problem?

Not really, it would appear.

Of course, there is the Government’s Intergenerational Report for the long view. While the IGR is well publicised —we covered it too, see the links below —there is another Canberra outlet that runs the number for the next few decades and finds that things will probably be alright.

The Parliamentary Budget Office published its ‘Beyond the budget 2023-24: Fiscal outlook and sustainability’ report in June, analysing long-term fiscal sustainability to 2066-67. Its definition of fiscal sustainability is:

….the government’s ability to maintain its long-term fiscal policy settings indefinitely without the need for major remedial policy interventions. This means that governments need to continue to act but that, in general, historical approaches to borrowing and repaying debt can be maintained, while keeping taxation and spending within reasonable and expected bounds.

In practice, this means:

…. the fiscal position to be sustainable if the debt to GDP ratio is expected to be stable or trend downwards over the long term. Such circumstances provide governments the fiscal space to pursue their long-term policy objectives and to support sustainable economic growth. It allows flexibility for governments to respond to changes in economic conditions, including downturns, either through automatic or discretionary mechanisms.

(Emphasis added)

That is, to understand whether the Commonwealth’s finances are sustainable over the long‑term, we need to have a view about how the debt-GDP ratio might evolve over time, which is captured by a relatively simple equation:

Tomorrow’s debt-GDP =

Today’s debt-GDP * (Interest rate – Economic growth)

– Primary Balance (as % of GDP)

The more mathematically inclined reader may find the detailed algebra interesting. For the rest, let’s unpack the intuition.

Debt-to-GDP ratio is composed of two terms: debt, and GDP. The existing stock of debt accumulates because of interest rate, while economic growth is the rate of change of GDP over time. When the rate of interest on government debt is higher than economic growth, the ratio rises over time because the numerator is growing faster than the denominator. The reverse is true when the economy is growing at a faster clip than the interest rate.

That is, the first term in the right-hand-side of the equation describes how the old debt is evolving over time. The second term, in contrast, describes the creation of new debt (or retiring of old debt) reflecting the government policy choices today.

Primary balance refers to the difference between government revenue and non-interest expenditure —stuff like public servants’ salaries, procurement, capital expenditure, transfers and subsidies: things that governments do to provide public goods and services. When a government runs a primary deficit, it needs to finance that deficit by borrowing —this adds to the debt-GDP ratio. A primary surplus, on the other hand, means the government has funds that can be used to pay down some old debt, reducing the ratio.

Given the above equation and the starting debt-GDP ratio, one can project the ratio into future using only three variables: interest rates, economic growth, and primary deficit. This may appear deceptively simple, but in fact the values one chooses for the three parameters require considerable judgment and country expertise.

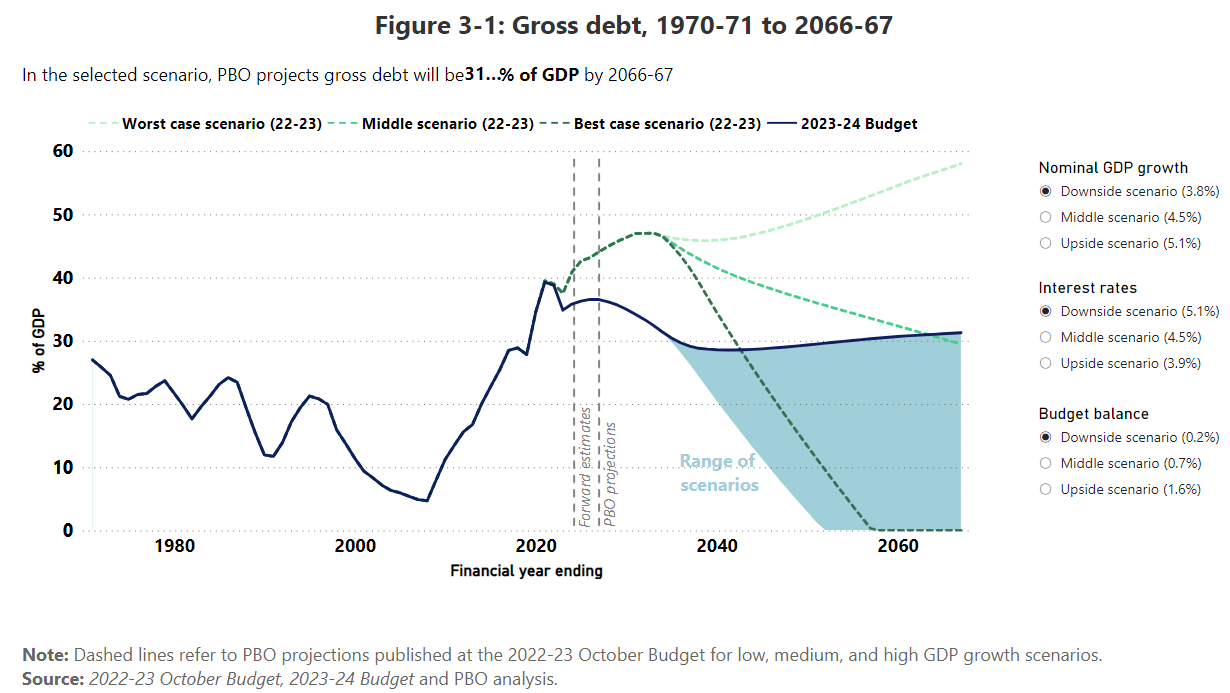

The PBO considers three possibilities —middle, upside, downside —for each of the three variables, yielding a total of 27 possible scenarios:

Their middle possibilities use historical averages and latest information from other sources such as bond yields or the Australian Bureau of Statistics analysis, with upside and downside reflecting plausible variations. Crucially, the middle-middle-middle scenario is not a central projection —the PBO is not making any judgment that any scenario being more likely than the others. Rather, the 27 scenarios together present a plausible range over the next few decades.

And they find that even in the worst-case-scenario, gross debt is relatively stable around 31 percent of GDP (their dynamic chart allows the reader to choose parameter values, check it out, it’s cool!):

The long-run stability of the debt-to-GDP ratio implies that governments have the flexibility to address policy problems, each requiring their own individual trade-offs. Overall, however, as far as the Commonwealth public finances are concerned, it seems that:

Previous posts on public finances

Budget forecasts are usually not-very-accurate

Is the recent Commonwealth Budget inflationary, and does it matter?

The fiscal outlook is set to worsen in the coming years

How to make the next Intergenerational Report relevant for the next generation

The Budget may well envisage a slight fiscal tightening in 2023-24

The Australian budget is being buoyed by cyclical factors, but is in structural deficit

The IGR: a little more action?

Rigorous, impartial, useful ... but it's important to remember what it isn't and think about what it could become

Further reading (that may or may not be relevant anything we have written or may write about)

Unlearning the macroeconomic lessons of the 2010s

Noah Smith, 23 Dec 2022

Interest Rates Likely to Return Toward Pre-Pandemic Levels When Inflation is Tamed

How close will depend on the persistence of public debt, on how climate policies are financed and on the extent of deglobalization

Jean-Marc Natal, Philip Barrett, April 10, 2023

Suicide rates for girls are rising. Are smartphones to blame?

Hospitalisation rates for self-harm have increased by 140% since 2010

The Economist, 3 May 2023

The History and Future of the Federal Reserve’s 2 Percent Target Rate of Inflation

The Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target rate of inflation is not strictly empirically derived. Should it modify this target moving forward?

Roger W. Ferguson Jr. and Upamanyu Lahiri, 15 June 2023

Paul Krugman, 22 Aug 2023

The Star-ry Night in Jackson Hole

Central bankers will soon travel to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, as they do every year, to think big thoughts on monetary policy and relax under the stars.

Claudia Sahm, 23 Aug 2023

How Is Our Current State Different from What We Would See in a Successful Inflation Soft Landing?

It isn't. It isn't different at all...

Brad Delong, 15 Sep 2023

Lessons from a century of inflation shocks

Robin Wigglesworth, 18 Sep 2023

The winners and losers in the 2023 New South Wales budget

Catherine Hanrahan, 19 Sep 2023

The Fed's Bullishness Is Pushing Up Rates

The latest projections suggest that the economy has more underlying momentum than previously believed *and* that there is less need to crush the job market to bring inflation back into line by 2026.

Matthew C Klein, 22 Sep 2023