SOMEWHERE OVER THE RAINBOW, THERE IS A BUDGET SURPLUS

Budget forecasts are usually not-very-accurate

According to the Budget Papers, the Commonwealth Government is estimated to run a budget (underlying cash) surplus of $4 billion in the financial year that will end on 30 June. This compares with an underlying cash deficit of $37 billion that was expected at the October 2022 Budget. This $41 billion turnaround reflects $1 billion of policy decisions that would have widened the budget deficit, and $42 billion of ‘parameters and other variations’ —that is, the stuff that the Government has no direct control over, such as surging commodity prices, wages and prices inflation, and jobs growth.

How much should a new government be credited for a budget surplus that wasn’t expected previously? This ‘policy decisions’ versus ‘parameters and other variations’ decomposition —which is described in the Table 3.2 of the Budget Statement 3 of Budget Paper 1 —is a good place to start in answering that.

Of course, this assumes that the Budget surplus will, in fact, materialize. With ten months of data, one might think the surplus is in the bags. One ought to be cautious. The budget surplus is expected to be 0.2% of GDP. Since the 1990-91 Budget, the average absolute forecast deviation on the current year budget estimate is 0.4% of GDP, with a standard deviation of 0.54 percentage points. In only two years in that period —1996-97 and 2016-17—did the current year budget estimates come to pass. That said, only in six of the 33 occasions was the current year budget estimate worse by more than 0.2% of GDP.

That is, if history is any guide, there is a possibility that Jim Chalmers might yet not be the first Labor Treasurer since Paul Keating to deliver a surplus!

So much for the current year. What about the budget year?

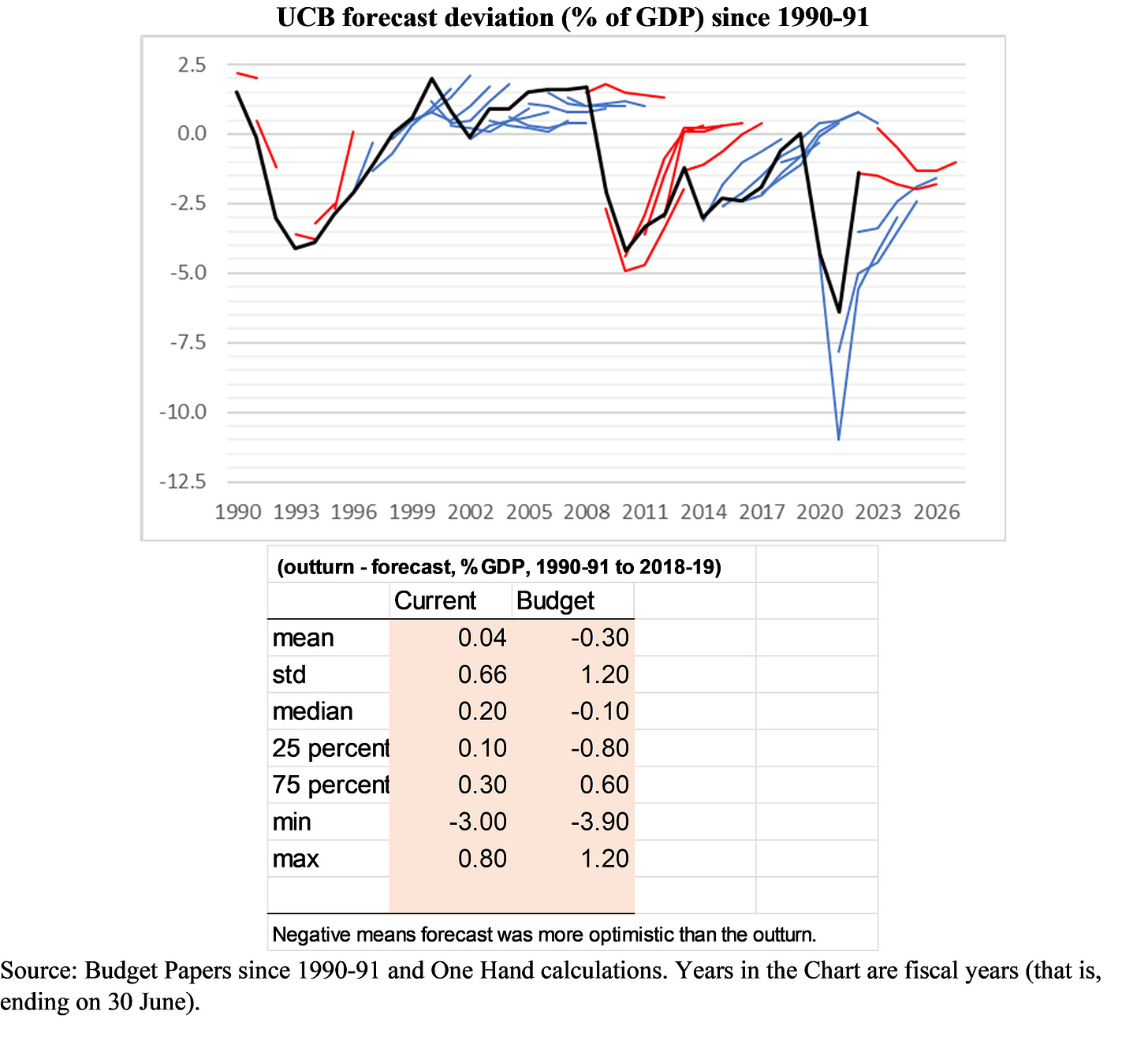

The chart shows the evolution of UCB against the budget forecasts since the 1990-91 Budget (which forecasted a 2% of GDP surplus for the budget year just before the economy went into a recession). The budgets are colour-coded with blue for the Coalition and red for the ALP. The table below that shows the statistical summary of forecast deviations for UCB over the business cycle spanning between the early 1990s recession and the pandemic (that is, the 1990-91 and 2018-19 Budgets).

The Government is forecasting a budget deficit of 0.5% of GDP in 2023-24. If next year turns out to be like the mean year of the last business cycle, the budget deficit could well be 0.8% of GDP. But if next year is like the median year, then the deficit could be 0.6% of GDP. If we end up with another Global Financial Crisis, the deficit could be 4.4% of GDP. On the other hand (yes, yes, I know we said there is only one hand…), next year could be like 1999-2000 or 2004‑05, when the budget bottom lines were 1.2% of GDP better than what was forecast. In fact, in 11 of the 29 occasions in that period, the budget outcome was at least 0.5% of GDP better than the forecast.

That is, if history is any guide, there is a possibility that Jim Chalmers might be the first Labor Treasurer since Paul Keating to deliver a surplus next year!

Of course, if there is a budget surplus next year, it won’t necessarily be the Government’s doing any more than a wider deficit won’t necessarily be its fault. Remember that policy decisions versus parameters and other variations? Underlying these budget forecasts are forecasts of government revenue and expenditures, which rely on macroeconomic forecasts of economic growth, composition of productions and incomes in the economy, employment and household consumption growth and wages and price inflation. Any number of reasons could throw those numbers off.

So, next time you hear any politician crowing about a surplus, or berating their opponent for a budget blowout, remember that these forecasts have been historically not-very-accurate, and there is no reason to expect this will change now.

Further reading (and watching, not necessarily related to the Budget, but we may post about them at some point)

Frank Ramsey—a philosopher, economist, and mathematician—was one of the greatest minds of the last century. Have we caught up with him yet?

Anthony GottliebApril 27, 2020

Budget Statement 8, Forecasting performance and sensitivity analysis, Budget Paper 1.

A DemTech Economic Agenda: Ten Steps Towards Collective Resilience, Noah Smith, 9 May 2023

How China measures national power, The Economist, 11 May 2023

The week began with a budget that tried to please everyone and ended with a political brawl, Laura Tingle, 13 May 2023