MONEY'S TOO TIGHT TO MENTION

Is the recent Commonwealth Budget inflationary, and does it matter?

Every government hopes to get a boost in the polls out of a budget.

A bad budget has a way of ending governments. Then Treasurer Joe Hockey failed the task in 2014 — in a budget that proposed to cut legal aid, raise Medicare co-payments and delay young people’s access to unemployment benefits by 6 months, among other measures — the defeat of which in the Senate provided a slightly more gracious path for then Prime Minister Tony Abbott to exit the top job than that provided more recently to Liz Truss in the UK.

That boost in the polls often comes through spending more. The general hope is that the recipients of spending will like that, and those that pay the taxes to fund it won’t notice until after the next election.

But, in the current environment, with unemployment rates at 50 year lows, the hope is probably also that mortgagees whose interest rates could rise if a budget were to cause inflation also won’t notice until after the next election.

This is a distributive impact. The most recent Albanese Government Budget needed to take a decision on how much of the burden of getting inflation back into the 2-3% target band should be borne by indebted households and businesses, and how much should be borne by other groups.

So is the latest budget inflationary?

Government spending decisions have been unusually restrained

The inflationary impact of a budget is a result of policy decisions taken. Commodity prices go up and down driving the business tax take, and employment and unemployment rates also move affecting labour income tax and welfare payments. By and large, these movements reflect global and domestic macroeconomic forces over which the Government of the Day has only modest control. In budget language, these are parameter variations.

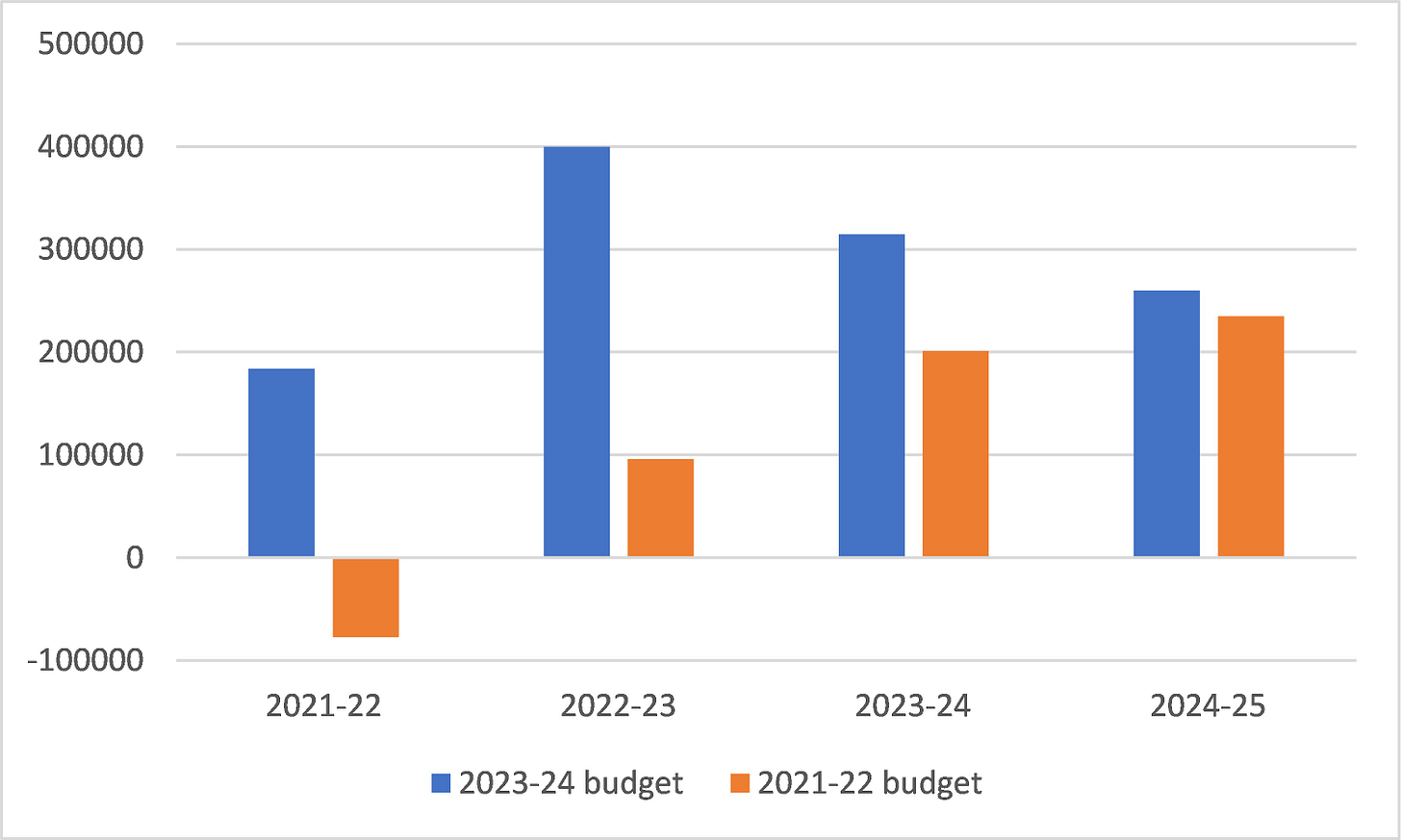

Macroeconomic forces have improved the budget bottom line over the three financial years to 2024-25 by roughly $250 billion. What is most remarkable is the restraint shown by governments of both stripe in spending these windfall gains.

Effects of parameter and policy changes on the underlying cash balance ($ billion)

So is the latest budget inflationary?

The short answer is: of course, yes. It’s fair to say that economists can’t agree on much, but by and large we all think spending more money in a low-unemployment environment is going to raise inflation.

The Albanese Government is giving money to people on welfare, renters and to relieve energy cost increases for low income households. By design, the recipients will mainly be people doing it tough, and the expectation is that they will spend it.

Much of the effect will likely flow through to inflation eventually. With unemployment at 50 year lows, the production side of the economy has only a limited ability to flex.

But the effect on inflation is small, and will be spread over a number of years. The overall additional government spend is small (broadly speaking, the effect of Labor policy decisions on spending amounts to less than 0.5% of GDP). And the inflationary effect will be spread out because not all of the additional money to households will be spent immediately, and the increase in demand will lead to wage negotiations with a lag, and so forth.

What this means is that the targeted increase in payments to welfare recipients will only marginally increase the probability of an interest rate rise that reduces the wellbeing of mortgagees.

Is that a good thing, or a bad thing?

Every budget is a product of its times.

Mr Albanese’s budgets have come amid tough economic times for many Australians. Low income households are facing acutely higher energy and food prices; mortgagees are feeling pressure of higher interest rates; renters are feeling the pressure especially when they move and bid for new properties. Australians in any of these three cohorts are doing it tough … and if you add up the private renters, and the mortgagees and the low income households … that’s most Australians.

First, in these circumstances, it is clear that any government would have delivered a cost-of-living relief package of some shape. A comparison against a ‘no policy change’ scenario — the convention which is understandably used in budget papers — isn’t a fair assessment of whether the policy decisions were tight or loose.

Second, the effects of this budget on inflationary pressures will play out over a number of years. With RBA modelling suggesting perhaps a 50:50 chance of the economy entering recession over the next year or so, there is a material chance that some of the stimulatory effect will land in the economy at a time when it may help steady, rather than overheat, the economy.

Third, massive movements of people into Australia are likely to put downward pressure on both wage and price inflation (outside of housing). Many of these migrants are university students who will be looking for work in the cafes and pubs and restaurants that have been crying out for staff in recent times, with the ABS finding vacancies in these industries up 300% on pre-pandemic levels. This will tend to lower inflation and mitigate concerns about this budget being inflationary. More to come on this topic.

Net overseas migration estimates

To sum up, when you ask an historian what are the consequences of the French Revolution, you should expect the response ‘It’s too early to tell’. Asking an economist about the inflationary impacts of the most recent budget, you may receive a similar reply.

It’s fair to say, there is greater than average uncertainty in macroeconomic forecasts right now. A strength of the most recent budget, which spent only a fraction of the improvement in the fiscal balance, is that future budgets or mid-year economic updates will be able to better respond to economic conditions as they unfold.

Many households are tightening their belts. Federal governments have been loosening their belt only one notch at a time. And that is probably a good thing.