“But this long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task, if in tempestuous seasons they can only tell us, that when the storm is long past, the ocean is flat again.” —Keynes

“The evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interred with their bones.” —Shakespeare putting words in Marc Antony’s mouth

Okay, a bit too dramatic perhaps, but Treasury macroeconomists probably do need to take a longer-term view than their Reserve Bank or market peers.

Market macroeconomists tend to think about the impact of an event —the latest data release, announcement by someone in authority, news —on the financial markets. Their attention span is days, if not hours. For most RBA macroeconomists, the time horizon of particular interest is months and quarters, perhaps a year or two but seldom more. For them, the question is, how does a shock affect the economy in general, and inflation in particular, with the answer shaping the monetary policy decision.

Treasury macroeconomists need to think in terms of years. Most government programs are implemented over years. Taxes and expenditure settings are expected to remain unchanged for even longer. Therefore, Treasury macroeconomists need to understand how a shock might affect not just revenues and expenditures currently, but also how might the resultant change be carried forward into the medium and longer term.

Needless to say, many things that might move the stock market today would in all likelihood not matter to public finances a year or two out.

Hmm. Does it mean the Treasury types are more likely to look like this than their big city peers?

I digress.

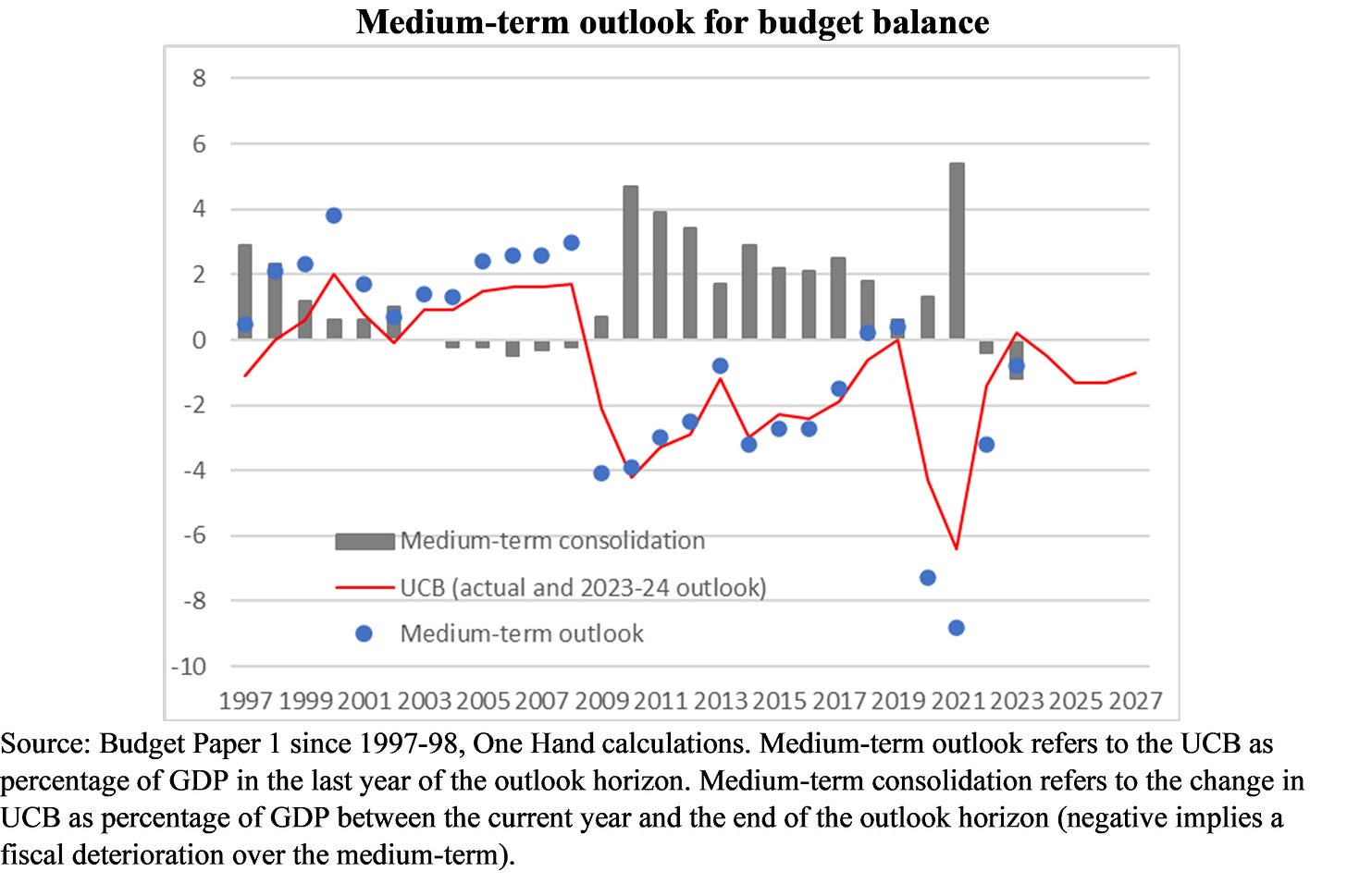

This longer-term focus is the reason why since 1997, Australian Budgets have provided fiscal outlook over at least four years. Specifically, in addition to the estimate of the current year fiscal outcomes and forecasts of the budget year, Budgets also contain outlooks for the three following years. For example, while a surplus of 0.2% of GDP is estimated for 2023-24, a 0.5% of GDP deficit is budgeted for in 2023-24 and then the deficit is expected to widen thereafter before narrowing slightly to be at 1% of GDP in 2026-27.

That is, the medium-term fiscal outlook is for a 1.2% of GDP deterioration in budget balance.

Of course, it is impossible to forecast in any meaningful way what shocks —the tempests that Keynes speaks of —will hit the economy over the next few years. The medium-term outlook is, usually, by assumption where the economy is at full employment and growing at its trend pace with inflation contained within the RBA’s target. That is, the medium-term is one where, to use Keynes’s words, the storm is long past, the ocean is flat again.

That is, the medium-term 1.2% of GDP worsening of the budget balance occurs even after the effects of the current shocks are supposed to have percolated through the economy.

This medium-term fiscal deterioration is quite unusual by historical standards, as illustrated in the Chart below.

Firstly, this is the worst fiscal deterioration over the medium-term since 1997, when the practice began.

Secondly, it is quite different from the previous run of fiscal deterioration that happened in the 2000s. Back then, Treasurer Peter Costello announced a string of budget surpluses on the back of the mining boom, with healthy surpluses still projected at the end of the outlook horizon despite the medium-term narrowing of the surplus because of tax cuts and new spendings. This is not the case time around. The medium-term outlook is not just a worsening of budget balance, it is also one of a deficit at the end of outlook horizon.

And this brings us to the third way this time is different —in the past, medium-term outlooks of a budget deficit were accompanied by significant fiscal consolidation over the medium‑term, not deterioration.

There has been a lot of discussion about the near-term effects of the budget, and perhaps not enough about the medium-term outlook. Do we have a looming fiscal problem? Are we reaping economic and fiscal benefits that cannot endure? Salvaging the flotsam and jetsam of a tempest that will ultimately wreck the whole ship?

Can we go the distance, handle some resistance?

I guess we’ll find out in the long run!

Further reading (that we have found interesting without necessarily agreeing or disagreeing with)

The bill for the future looms ever larger

Henry Curr, 22 Oct 2022

Rather than exerting useful discipline, they are constraining government investment

Andy Haldane, 16 May 2023

The discipline, willingly or not, has inhaled his influence

18 May 2023

No, but in a few big cities it might be.

Noah Smith, 27 May 2023

The solutions to Australia’s housing crisis are actually quite obvious

Analysis of recent figures shows the number of housing approvals has not kept pace with the nation’s rising population

Greg Jericho, 1 June 2023