About a month ago, Ben explored whether the 2023-24 budget is expansionary (TL/DR: yes, but probably not a bad thing all things considered; do read the whole thing). Another way to explore whether a budget is expansionary is to check the trajectory of the cyclically adjusted or structural budget balance over time.

A cyclically adjusted or structural budget balance strips out the effect of the business cycle on revenue and expenditure. During an economic slowdown, for example, the budget balance would worsen even if there were no explicit policy measures. With progressive taxes on labour income, as the labour market worsens (job losses, paring back of work hours, weakening wages growth), tax receipts might dip relative to GDP. Meanwhile, countercyclical expenditures such as unemployment benefits would rise even as GDP slows. The budget balance would worsen through the operation of the ‘automatic stabilizers’. But this doesn’t actually mean the budget itself is expansionary in the sense that the worsening of the balance would reflect the economic conditions.

The idea behind the cyclically adjusted or structural balance is to consider the fiscal stance after adjusting for the economic conditions.

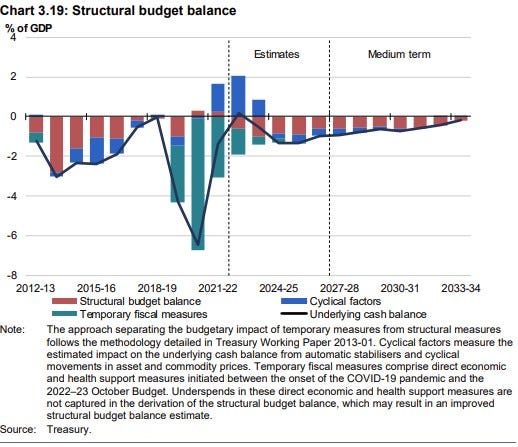

Hidden in page 131 (Budget Statement 3) of the Budget Paper 1 is the official estimate of the structural budget balance, which is reproduced below. According to this estimate, the budget might not be expansionary after all!

Treasury adjusts the budget balance (the underlying cash balance) for cyclical factors (the blue bars, capturing the automatic stabilisers and cyclical movements in asset and commodity prices) and direct economic and health support measures that were temporarily put in place during the pandemic (the green bars). Once both effects are accounted for, the red bars represent the ‘structural balance’.

The exact numbers don’t appear to be available, but eyeballing the chart, it’s clear that the red bar goes from something close to negative half of a percent of GDP in 2022-23 something close to negative one percent of GDP in 2023-24 —that is, Treasury estimates that the structural budget deficit is set to widen by something like half a percent of GDP in 2023-24.

That is, the budget is somewhat expansionary.

Or is it?

Now, there is a good reason why these temporary measures should be explicitly counted out to derive the structural balance —doing so helps us understand whether the current policy setting (revenues and expenditures) add to or detract from sustainable public finances. Recall, I asked whether the medium-term 1.2 percent of GDP worsening of the underlying cash balance means we have a medium-term fiscal problem. Well, according to the above chart, Treasury’s best guess is for structural deficits well into the 2030s.

That is, yes, we may well have a long-term fiscal problem.

Wait, Treasury’s not that good at forecasting one year out, how confident should we be about these structural balance projections ten years out?

The cynical answer is, not very confident. But a more nuanced answer would require a comparative analysis of Treasury’s methodology to derive these estimates with the Parliamentary Budget Office’s approach. Further, to the extent that both approaches rely on some measure of the output gap or full employment, the Reserve Bank’s approach should also be considered. And all of that, ultimately, would require getting a better grasp of the underlying productivity trend.

All of that might be explored in a future post, or a few posts.

For our purposes, however, does it make sense to ignore the green bars if we want to know whether the budget is expansionary now?

Yes, these measures are temporary and will not detract from fiscal sustainability in the long run. But they are adding to demand currently independent of the business cycle, and if we want to know whether the budget is expansionary in 2023-24, we would want to know whether they are adding more or less to demand next year relative to this year. That is, we would want to add up the red and green bar in the above chart and compare the 2022‑23 value with that of 2023-24.

Again, eyeballing the chart, we get a ‘cyclically adjusted’ deficit of nearly 2% of GDP in 2022-23 narrowing to something like 1½% of GDP in 2023-24. That is, abstracting from the cyclical effects, but including the withdrawal of the temporary pandemic measures, the budget envisages a small fiscal contraction.

It's tight like that!

Further reading (not necessarily related to this post, but something we may explore in future)

Adam Tooze, 15 Oct 2022

Henry Mance, 16 Jan 2023

Divya Kirti, Maria Soledad Martinez Peria, Prachi Mishra, Jan Strasky

February 27, 2023

Australia has faced down China’s trade bans and emerged stronger

Economist, 23 May 2023

Claudia Sahm, 26 May 2023

Noah Smith, 11 Jun 2023

Gareth Hutchens, 25 June 2023