BEYOND RENT CONTROL

Empirical evidence suggests that rent control could hurt those it is intended to help

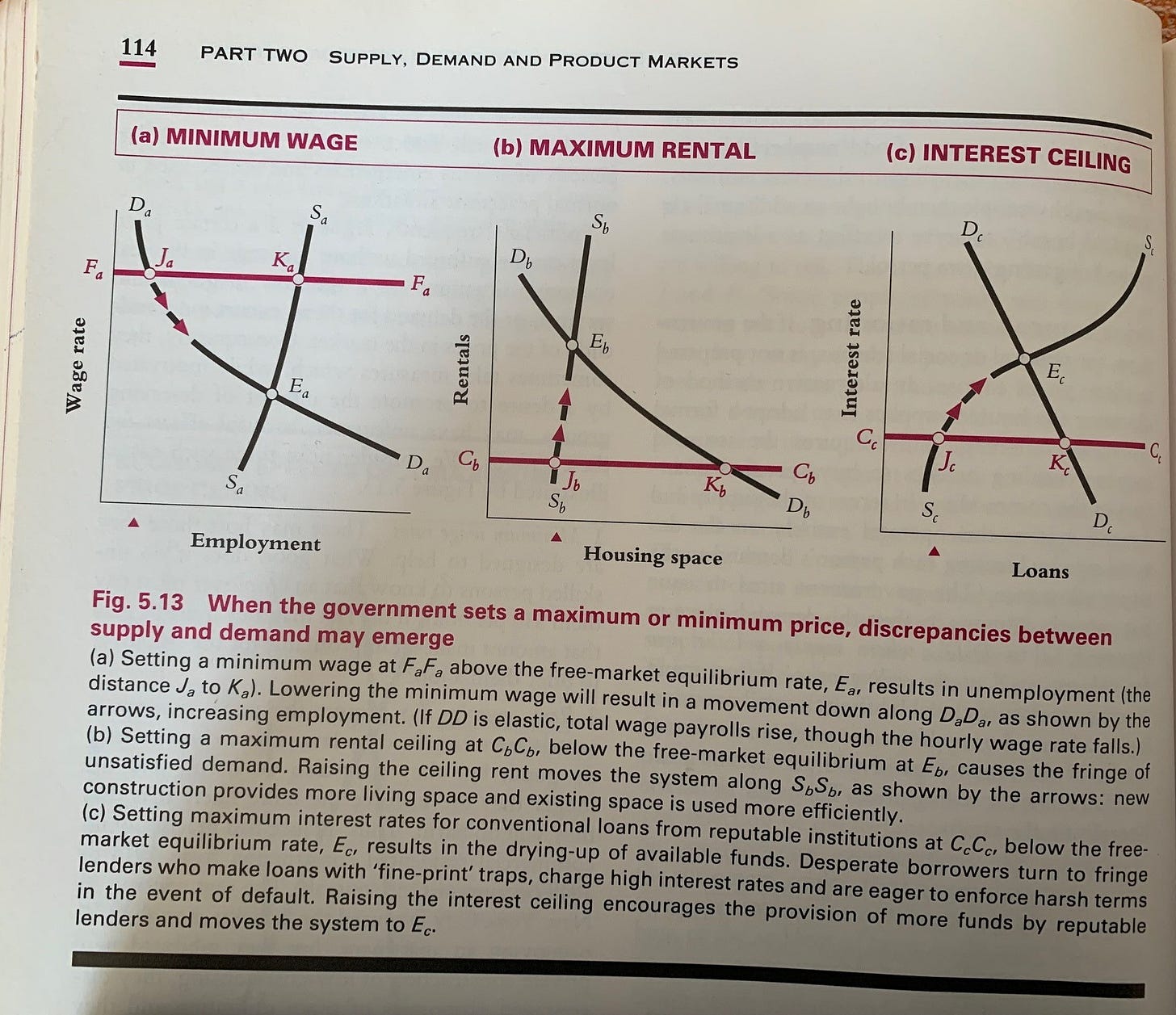

My first undergraduate econ textbook was the Australian edition of Samuelson and Nordhaus et al(1). That was almost three decades ago. We learnt about the effects of government enforced minimum or maximum price in pages 113-14. Setting a maximum ceiling, we were taught, would create a situation of excess demand.

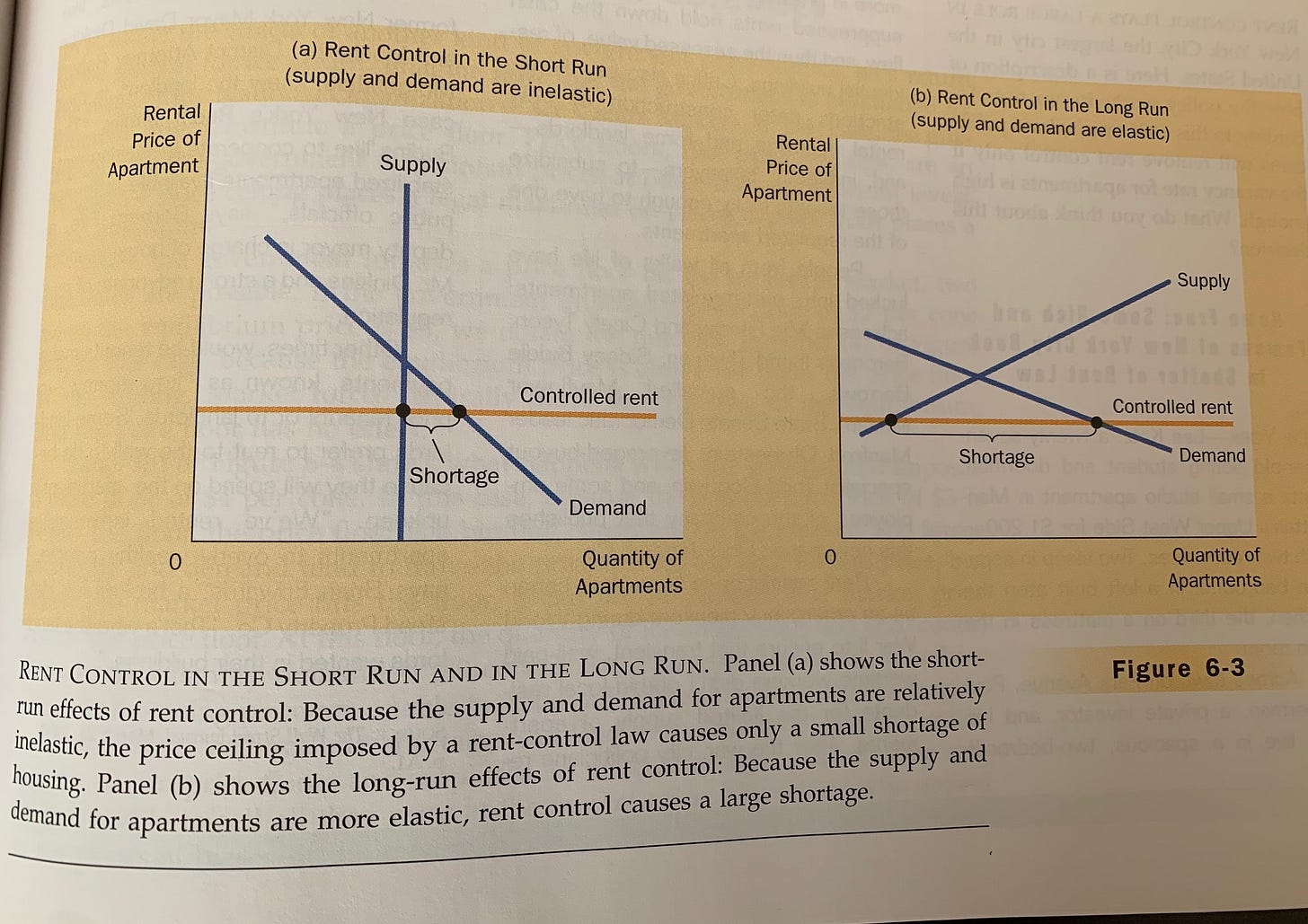

A few years later, I tutored undergraduate microeconomics at Sydney, UNSW and ANU. Mankiw was the textbook most commonly used. The discussion on rent control appears on pages 115-17, showing how the effects vary in the short and long term because of elasticities —since supply and demand are more elastic in the longer term, the shortage caused by rent control is also larger in the long-term.

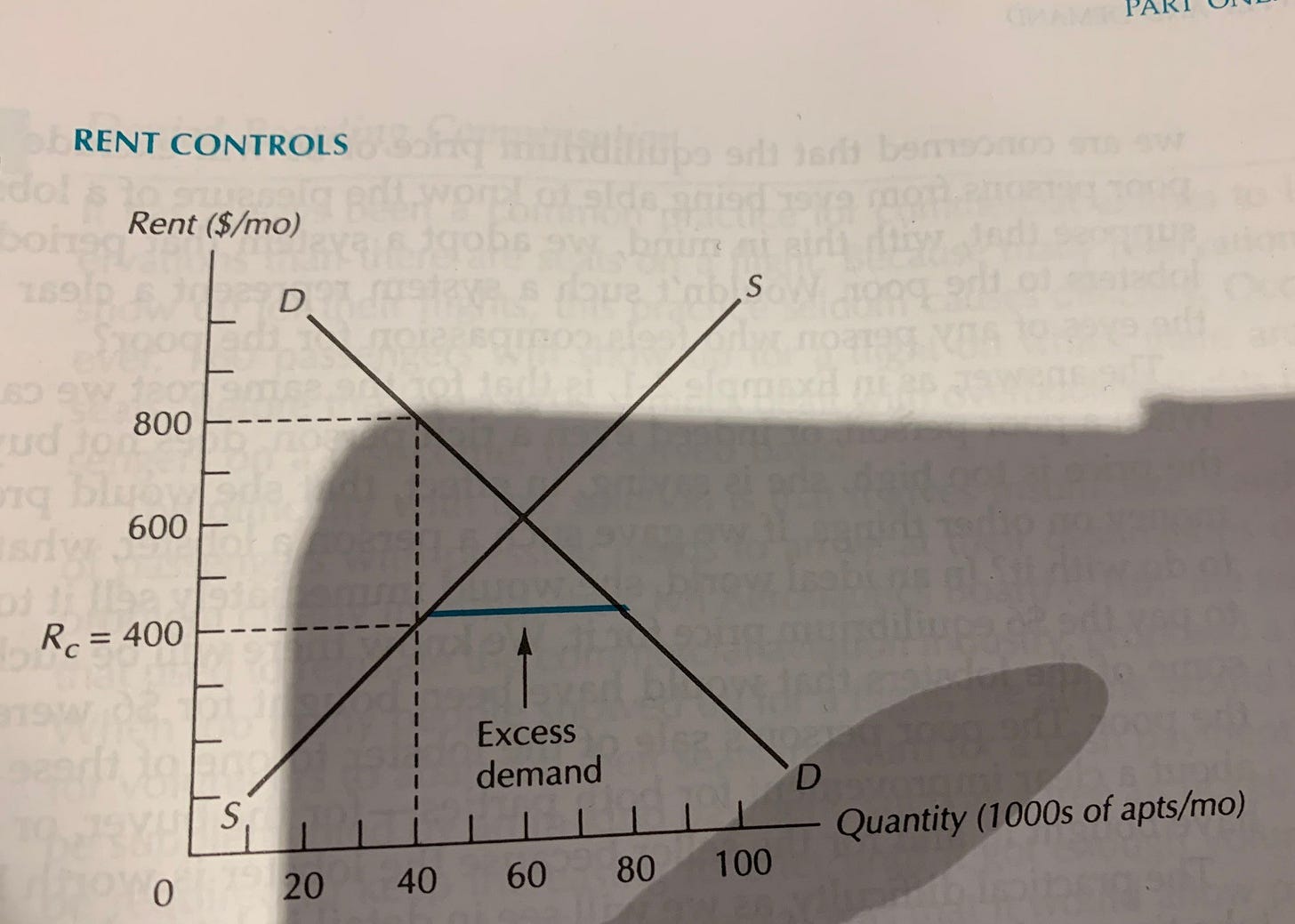

I learnt, and taught, exercises such as calculating the shortage in the following scenario diagram:

The last time I was in an undergrad micro class room was over two decades ago.

There is an excerpt from a 1994 Wall Street Journal article in the Mankiw textbook titled ‘Home Free: Some Rich and Famous of New York City Bask in Shelter of Rent Law’ about rent control in the Big Apple. The anecdotes in that article echo the examples Milton Friedman and George Stiegler used in their classic 1946 article titled ‘Roofs or Ceilings? The Current Housing Problem’. Their conclusion:

Rent Ceilings, therefore, cause haphazard and arbitrary allocation of space, inefficient use of space, retardation of new construction and indefinite continuance of rent ceilings, or subisidization of new construction and future depression in residential building.

Of course, rent control is a matter of live policy debate in Australia, and perhaps elsewhere too (in America and Britain, for example). Now, my first reaction might have been ‘whoa, this is 2023 and we are still debating rent control’. But I did pause and think ‘maybe there is more to this idea than what’s in the textbooks’.

I mean, the same textbooks also taught us that minimum wages would cause unemployment. And we now have an empirical literature that questions the simple textbook model, with David Card winning a Nobel prize for pioneering that work. Indeed, the textbooks also have lot of reasons why the simple competitive market supply-demand framework might not work in practice. The textbooks I used at university were written at a time when much of the empirical work on the minimum wage was still at an early stage. Perhaps there has also been an empirical literature on rent control in the past couple of decades, showing that the real world works differently from the textbook?

So I dug around a bit, and found a succinct Brookings paper comparing two American studies: one by David Autor and colleagues on the removal of rent control in Cambridge, Massachusetts(2); the other by Rebecca Diamond and colleagues about expansion of rent control in San Francisco (3). The conclusion of both papers taken together:

Rent control appears to help affordability in the short run for current tenants, but in the long-run decreases affordability, fuels gentrification, and creates negative externalities on the surrounding neighborhood

Then I came across a meta-study by Konstantin Kholodilin of DIW, a German think tank. Kholodilin reviews 92 studies for 36 countries using various different econometric techniques over the period 1967 to 2022. Then he runs a meta-regression of these analyses. His conclusion:

… although rent control appears to be very effective in achieving its main goal — lower rents — it also results in a number of undesired effects, for example, lower mobility and residential construction.

That is, as best as we can tell, rent control seems to have the kind of effect one would expect from the textbook model —good for the current tenants in the short term, but with distortions in the long run that seems to make the housing situation worse!

If we are to seriously tackle housing issues, we need to think beyond rent control. Build more houses? Absolutely. Enhance tenants’ rights? By all means. Curb immigration? Perhaps. Two year rent freeze? No, that will only hurt the very folks that the policy is intended to help.

(1) Samuelson P, Nordhaus W, Richardson S, Scott G, and Wallace R, Economics, 3rd Aust. edition, Vol. 1, Microeconomics, McGraw Hill, Sydney, 1992. Seems to be not available online, which probably makes my copy vintage!

(2) Autor DA, Palmer CJ, Pathak PA, ‘Housing Market Spillovers: Evidence from the end of rent contol in Cambridge, Massachusetts’, Journal of Political Economy, 122(3), June 2014.

We measure the capitalization of housing market externalities into residential housing values by studying the unanticipated elimination of stringent rent controls in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1995. Pooling data on the universe of assessed values and transacted prices of Cambridge residential properties between 1988 and 2005, we find that rent decontrol generated substantial, robust price appreciation at decontrolled units and nearby never-controlled units, accounting for a quarter of the $7.8 billion in Cambridge residential property appreciation during this period. The majority of this contribution stems from induced appreciation of never-controlled properties. Residential investment explains only a small fraction of the total.

(3) Diamond R, McQuade T, and Qian F, "The Effects of Rent Control Expansion on Tenants, Landlords, and Inequality: Evidence from San Francisco." American Economic Review, 109 (9): 3365-94, 2019.

Using a 1994 law change, we exploit quasi-experimental variation in the assignment of rent control in San Francisco to study its impacts on tenants and landlords. Leveraging new data tracking individuals' migration, we find rent control limits renters' mobility by 20 percent and lowers displacement from San Francisco. Landlords treated by rent control reduce rental housing supplies by 15 percent by selling to owner-occupants and redeveloping buildings. Thus, while rent control prevents displacement of incumbent renters in the short run, the lost rental housing supply likely drove up market rents in the long run, ultimately undermining the goals of the law.

Further reading

Previous posts on housing issues:

Far more housing is needed than forecast even a couple of months ago, 5 June

Courting the homeless people the Greens sold out, 19 June

We need to manage social housing better, 26 June

Other interesting housing pieces (that we may or may not agree with)

The solutions to Australia’s housing crisis are actually quite obvious

Analysis of recent figures shows the number of housing approvals has not kept pace with the nation’s rising population

Greg Jericho, 1 June 2023

Australia can’t build its way out of housing crisis

Leith van Onselen, 16 July 2023

Are Scotland’s rent controls working?

Neither tenants nor landlords are happy as the country’s rental crisis deeepens

Lukanyo Mnyanda, 3 Aug 2023

Other interesting stuff we have been reading, and may or may not (have) writ(t)e(n) about at some point.

We won’t solve the teacher shortage until we answer these 4 questions

Hugh Gundluch, 5 May 2023

Your job is (probably) safe from artificial intelligence

Economist, 7 May 2023

Reducing Inflation along a Nonlinear Phillips Curve

Erin E Crust, Kevin J Lansing, and Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau, 10 July 2023

If this is a bad economy, please tell me what a good economy would look like

Noah Smith, 31 July 203

6 reasons Australians don’t trust economists, and how we could do better

Peter Siminski, 8 Aug 2023

Australia’s new development aid policy provides clear vision and strategic sense

Melissa Conley Tyler, 8 Aug 2023

Why are groceries so expensive?

Paul Krugman, 8 Aug 2023

Productivity Commission boss offers cure for APS ‘system inertia’

Melissa Coade, 24 Aug 2023