The U.S. President declares annually before Congress that the State of the Union is strong. It’s a convention that even Donald Trump stuck to.

Clearly, the Australian National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation (NHFIC) is bound by no such convention. Indeed, in its recent State of the Nation’s Housing report, published 3 April, it provided quite the opposite assurance.

The state of Australian housing is weak.

About the experience through the pandemic:

‘Lower population growth would have normally been expected to lead to slower rates of household formation during the pandemic. But over the course of 2021 and 2022, lockdowns and work from home arrangements meant there was a premium on space and vacancy rates plummeted sharply to record lows’

Of course, another interpretation is that housing supply coming on line at that time was designed with earlier, high migration rates in mind. Net, migrants left Australia during the pandemic. So there was more space available and household size fell as people spread out.

They continue:

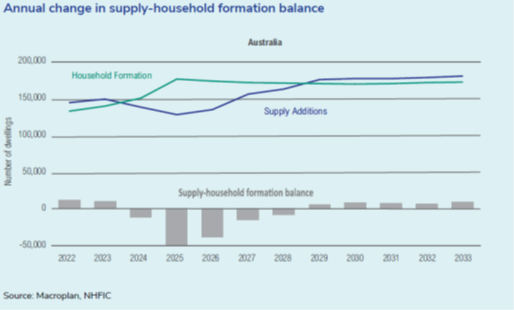

‘Based on revised Centre for Population data, net overseas migration is expected to recover to pre-pandemic levels of around 235,000 in 2022-23 (up from [a previous estimate of 180,000] … while NHFIC expects supply additions (net of demolitions) to be 148,500 in 2022-23, and then fall to around 127,500 in 2024-25… [overall] NHFIC expects the cumulative gap between new household formation and new supply will be around -106,300 dwellings over the five years from 2023 to 2027.‘

So now the reverse process is unfolding, with the volume of housing supply coming online designed to suit far lower migration rates.

NHFIC forecasts of a deficit in housing supply

Source: NHFIC.

That’s the good news, folks …

It turns out that NHFIC’s forecasts are wildly optimistic.

What we now know is that the deluge of migrants is going to be far, far higher than NHFIC assumed. And at the same time, housing starts have plummeted to record lows.

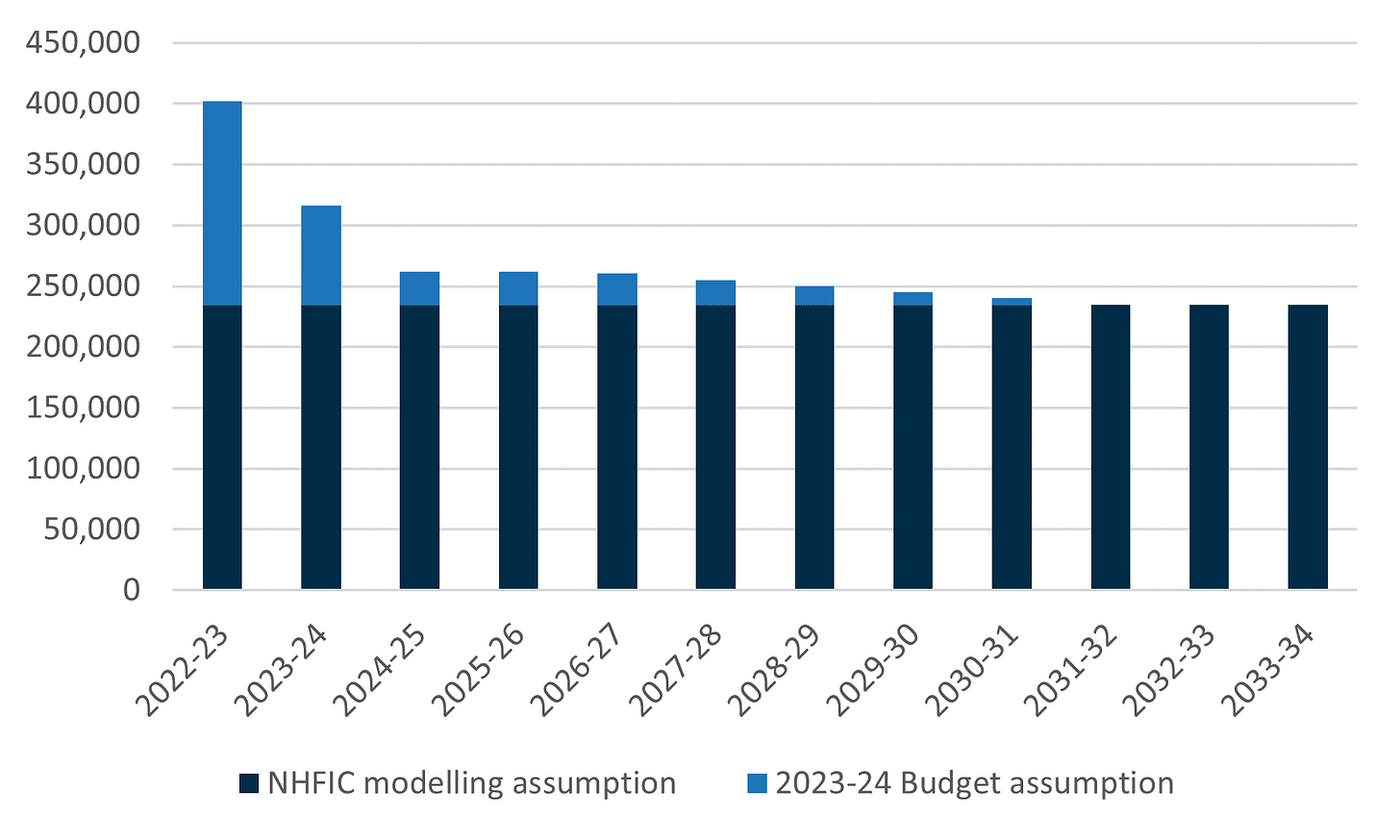

On migrant numbers, the most recent Australian Government forecasts are for about 377,000 more migrants to enter Australia than assumed in the NHFIC modelling. These additional migrants are front-loaded with about 250,000 additional migrants arriving in the current and next financial years.

Making the blandest of possible assumptions — that migrants have a preference to live in households of about the same size as other Australians, which is typically about 2.5 people per dwelling — the need for additional housing is about 100,000 dwellings above what NHFIC forecast over the next two years, and a total of about 150,000 dwellings more over the next decade.

That is, a reasonable assumption is that we have a housing shortfall of closer to 250,000 dwellings rather than NHFIC’s published estimate of about 100,000 dwellings, over the coming 5 years or so. (As an aside, one could pause to wonder why NHFIC would put out housing modelling 4 weeks ahead of a Federal Budget that was inevitably going to upgrade migrant estimates.)

Net Overseas Migration – NHFIC assumptions vs 2023-24 Budget Assumptions

Source: Australian Government Budget and NHFIC.

And that is still the good news, folks …

Meanwhile, residential construction data have come in weak. The April 2023 outturn for new approvals was down about 30 per cent from December 2022 numbers and at its lowest level since April 2012. Commencements and completions will follow in turn.

These are noisy data series. But it clearly isn’t just noise right now. Rapidly rising interest rates have deterred potential investors, and meanwhile residential builders are going to the wall (so to speak) due to inability to service fixed price builds amid rising input and labour costs. Most likely approvals will continue to fall, and completion times will extend.

Residential approvals, commencements and completions

Source: ABS.

Where to from here?

The result is more people chasing less housing than would have been anticipated even a couple of months ago.

RBA Governor Phil Lowe giving testimony before the Senate pointed to the role the price (that is, rent) mechanism will play. Young people will be slower to move out of home (no analysis was proffered of implications for parents, nor for the abortive path to adulting for young people). Some people will give up a home office and instead take a flat mate.

I’m not sure there are a lot of home offices waiting to be given up by university students … this is what $350 a week buys you in Sydney (albeit with part board):

Rents are going to need to rise a long way to drive the economization on housing the RBA Governor was pointing to.