Is it what you do that defines you?

Exploring an interesting theory with limited empirical support and potentially important policy implications

Both the one-handed fellows writing for you had left the APS to pursue more fun projects at an academic institution north of the Treasury, where they encountered various administrative hoops and rigmarole, leading one to quip that many of these administrators were perfectly nice people doing completely pointless tasks in order to get promoted so that they could supervise other nice people doing pointless tasks.

It is in this context that David Graeber’s theory of ‘Bullshit Jobs’ came up, which led to further reading, and now this post.

I will start with a brief summary of the theory, which has five testable propositions. Then I will discuss a paper that tested these propositions. While most of the propositions don’t seem to be supported empirically, putting in doubt Graeber’s main theory, there are potentially important policy implications, which will also be briefly touched upon. The reference is at the end.

David Graeber was an anthropologist, specialising in ‘economic anthropology’ — the academic discipline that seeks to understand economic behaviours and relationships against the backdrop of broader cultural, historical and geographic factors. He first wrote about ‘Bullshit Jobs’ in a 2013 essay. These were jobs that are “so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious that even the employee cannot justify its existence”. In a follow up 2018 book, Graeber elaborated further that these jobs are a result of ‘managerial feudalism’, which emerged because of neoliberalism and globalisation.

According to Graeber, the economies of capitalist democratic west were based on industrial capitalism until the 1970s. In industrial capitalism, the ruling class of capitalists derived their wealth from making and trading goods and services. Therefore, most jobs entailed making and moving stuff. They might have been ‘shit jobs’ in the sense that conditions were harsh or pay was low. But they were not ‘bullshit jobs’ in the sense that if these jobs were not done, stuff wouldn’t be made or moved, and thus wealth would not be created.

Since the 1970s, Graeber goes on to argue, the ruling class has moved on to using financialisation to appropriate wealth, while automation means a lot of non-bullshit (shit or otherwise) jobs are gone, and student loans brought on by neoliberal higher education policies mean educated people must work even if what they are bullshit. The result is ‘managerial feudalism’, which is an economic hierarchy where many, if not most, people hold pointless jobs so that they can get promoted and eventually partake in the appropriation.

The first figure below summarises the theory, while the second one are examples of bullshit and non-bullshit jobs according to Graeber (both figures are from the book).

One corollary of this theory is that since these bullshit jobs don’t create any stuff, if these jobs stopped, the society would not be any poorer.

Graeber goes on to posit five propositions that can be empirically tested.

And that’s what Magdalena Soffia (Cambridge), Alex Wood (Birmingham) and Brendan Burchell (Cambridge) did in a 2022 paper. According to Graeber, the employees themselves know whether what they are doing is bullshit. Therefore, Soffia, Wood and Burchell look at how people responded to the question ‘please select the response which best describes your work situation [. . .] you have the feeling of doing useful work’ (boldened by the authors — possible answers are a five point scale from always to never) in 2005-15 European Working Conditions Surveys.

Graeber’s five propositions, and their empirical evidence (or lack thereof), are summarised below (figures are from the 2022 paper).

The number of employees doing bullshit jobs is high (20–50%).

Not quite. Less than 5% of European workers thought their jobs were bullshit.

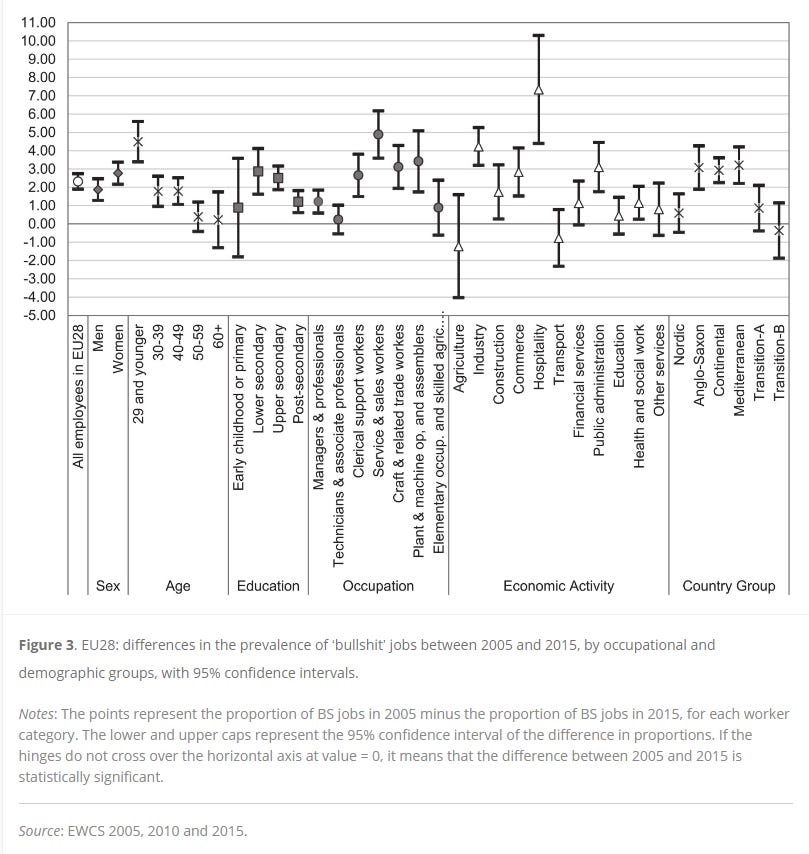

Bullshit jobs have been increasing rapidly over time.

No. It fell across Europe between 2005 and 2015 — see the figure below, again from the paper.

Some occupations (financial services, marketing, administration) have very high rates of bullshit jobs and others very low (refuse collectors, cleaners, farmers).

This is at the heart of Graeber’s theory. Let me quote the 2022 paper:

Based on his own intuition about what is useful and what is bullshit, and backed up by some of the anecdotes sent to him, he identifies occupations where a ‘preponderance of workers feel their jobs are pointless’ (Graeber, 2018: 64). In particular, he identifies some professional jobs as the ones that are most obviously BS jobs. For instance, he points out that ‘hedge fund managers, political consultants, marketing gurus, lobbyists, corporate lawyers’ (Graeber, 2018: 209) would not be missed at all if they disappeared, though if elementary school teachers and nurses, garbage collectors, and mechanics, bus drivers, grocery store workers, firefighters, or short-order chefs were to vanish, the effects would be devastating (Graeber, 2018: 209).

Evidence? Graeber is not quite right.

None of the occupations approached anywhere near the 20–50% levels Graeber’s theory is premised upon; moreover, the occupations where workers were most likely to feel their work was not useful were those Graeber maintains are not BS (i.e. refuse collectors and cleaners and helpers).

Young workers with higher education qualifications are more likely to be doing bullshit jobs due to student debts.

No. Authors “find a strong inverse relationship with education level (i.e. the more educated a young worker is the less likely they are to have a BS job), declining from 8.9% of those with only primary education to 3.6% of those with post-secondary education”.

Bullshit jobs cause ‘spiritual violence’ and poor mental health.

Yes. This is one part of the Graeber story that is supported by evidence.

To quote the paper:

Despite the prevalence of BS jobs being much lower than predicted by this theory, there is strong evidence that feeling that one’s job is useless is associated with poor psychological wellbeing. In the UK in 2015, workers who felt their job was not useful had WHO-5 wellbeing scores (M = 49.3, SD = 28.3) significantly lower than those who felt they were doing useful work (M = 64.5, SD = 21.7), and a similar gap was found in the EU28 sample.

Okay, so let’s summarise.

The underlying theory of managerial feudalism seems to lack empirical support for the first four of five postulates, at least in European data. It’s perhaps too soon to call it bullshit, because perhaps Graeber’s propositions hold true in American (or indeed Australian) labour markets.

This has policy implications. If a fifth to half the jobs were bullshit, then their disappearance would have made no difference to the society. If what you do is bullshit and causes you mental health problems, are you not better off not working and receiving some form of universal basic income?

Well, it would seem that there aren’t that many bullshit jobs in the first place, so no radical reorganisation of the society seems to be necessary. However, those who are employed in jobs that they consider useless do tend to suffer from mental health issues.

Of course, correlation is not causation. Is it these jobs that worsen the workers’ mental health, or those with mental health issues end up in these jobs? Clearly more work is needed to untangle this.

However, Soffia, Wood and Burchell do find correlations, and posit an explanation:

Our findings, therefore, suggest that workers feeling that their job is not useful, is not due to the job itself being ‘bullshit’ and the result of managerial feudalism but rather is a symptom of bad management and toxic workplace cultures leading to alienation.

…. alienation being most prevalent in declining blue-collar occupations which have traditionally been marked by hierarchical work organisation and a lack of discretion, participation and intrinsic skill-use.

This too has important implications. Across the western world, there is a populist political wave that harkens to a supposedly golden era of good jobs, non-bullshit jobs, jobs where workers knew that they were doing good stuff that made them feel great about life.

But those seem to be the jobs that are associated with alienation and mental health problems!

The theory of alienation is perhaps one idea that Marx proposed that is still relevant in our world. According to Marx, in a modern capitalist economy, each worker is just a cog in the big capitalist machine, and doesn’t have the autonomy to decide what they do, how they do it, and with whom it is done. It is this lack of autonomy that leads to alienation. (I am simplifying a lot, and I do not want to write about Marxist literature!).

There would be no alienation in a Marxist utopia.

In communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.

Meanwhile, in our world, it seems that for most of us, it probably is what we do that defines us. It’s a good thing that not many of us think what we do is bullshit. And for those stuck in such jobs, better management and improvement in working conditions — and not a radical social upheaval — could help.

Papers and books cited

Graeber D (2013) On the phenomenon of bullshit jobs: a work rant. Strike! Magazine 3: 10–11. Available at: https://www.strike.coop/bullshit-jobs/ (accessed 2 October 2019).

Graeber D (2018) Bullshit Jobs: A Theory. London: Penguin Random House UK.

Soffia, M., Wood, A. J., & Burchell, B. (2022). Alienation Is Not ‘Bullshit’: An Empirical Critique of Graeber’s Theory of BS Jobs. Work, Employment and Society, 36(5), 816-840. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170211015067

Further reading (that we may not necessarily endorse, and could potentially write about in future)

C Northcote Parkinson, 19 Nov 1955

Why the bullshit-jobs thesis may be, well, bullshit

David Graeber’s theory isn’t borne out by the evidence

The Economist, 5 Jan 2021

Mariana Mazzucato: ‘The McKinseys and the Deloittes have no expertise in the areas that they’re advising in’

The economist argues that consultants are hobbling the state’s ability to perform the role of economic motor

Henry Mance, 13 Feb 2023

Don’t bet against the ‘suitcase principle’ of white-collar work

Humans have a remarkable ability to create jobs for themselves — whatever the progress of technology

Sarah O’Connor, 30 May 2023

America's auto strike and a century of transition in the US car industry.

Adam Tooze, 30 Sep 2023

To Fight Populism, Invest in Left-Behind Communities

People living in “places that don’t matter” have seen quality jobs disappear, public services eroded, and their economic prospects rapidly diminish.

Diane Coyle, 28 Dec 2023

Liberalism is battered but not yet broken

Freedom is under threat in the west and elsewhere, but it must be defended

Martin Wolf, 10 Jan 2024

Anyone advocating neoliberal policies is now persona non grata in Washington, D.C.

Daniel W Drezner, 1 Fenruary 2024

Working from home and the US-Europe divide

Americans are no longer the rich world’s great office drones

The Economist, 1 March 2024

Labor market model paints an incomplete picture

The traditional economic model of how wages are set fails to reflect the real world

Suresh Naidu, 1 March 2024

Updated rules for international trade, coupled with stronger domestic policies, could make globalization more inclusive and sustainable

Adam Jakubik, Elizabeth van Heuvelen, 1 June 2024

Crisis memory, geopolitics and the risks of financial contagion

The question of how well we can deal with shocks in our future is not at all clear

Gillian Tett, 21 June 2024

Graeber’s theory…..

soffia et al….

Five testable hypotheses…

alienation….

policy implications….